#large dog urns

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ohan’Ali Dock West

(CC List + DL)

[Note: (1) If your sims keep taking off their shoes and you do not want them to, individually click the Charly Pancakes shoes, located within the primary bedrooms of both houseboats, to get the menu to turn it off. (2) There are mini fridges slotted into both kitchens!]

World Map: Sulani

Area: Ohan’Ali

Lot Size: 30 x 30

Capacity

Houseboat 1: 2 Bedroom (Up to 5 sims), 1 Bathroom (w/ bathtub), Kitchen, Living

Houseboat 2: 2 Bedroom (Up to 6 sims), 1 Bathroom, Kitchen, Living, Bar Room, 2 Entertainment Decks

Gallery ID: Simstorian-ish

Packs Needed

Expansion Packs

Cats & Dogs

Cottage Living

Get Famous

Get Together

Get To Work

Growing Together

High School Years

Horse Ranch

Island Living

Lovestruck

Snowy Escape

Game Packs

Dream Home Decorator

Realm of Magic

Spa Day

Star Wars: Journey to Batuu

Strangerville

Vampires

Werewolves

Stuff Packs

Home Chef Hustle

Laundry Day

Toddler Stuff

CC Used

[All credits go to the following creators for sharing their work with the community. It is greatly appreciated and I hope that you all have endless nights of the best sleep ever.]

Helpful Tip: Having Only What is Needed For CC Builds (Tumblr)

Amoebae: Pile in Carpet

Anye: Neomy (Rug)

AroundTheSims4: Awning Set

Awingedllama: Blooming Rooms Separated

Charly Pancakes: Lavish, The Lighthouse Collection

DSC: Fancy Table Setting

Felixandre: Soho Pt. 1 | 5 (CurseForge)

GUA Sims: Apricity (Curtains + Tracks)

Harrie: Brownstone Pt. 1 (Shelves), Coastal Pt. 5|8, Country Kitchen, Klean Pt. 2, Octave Pt. 2|3|4

House of Harlix: Bafroom (Hot Tub), Harluxe, Kichen, Kichen 2.0, Livin’ Rum, Orjanic Pt. 1 (Sliding Oak Door Medium), Orjanic Pt.2 (Rug)

KKB’s: JOMO Laundry

Max20: Closet Collection

Lili’s Palace: Folklore (Deco Wheel on Wall 1)

LittleDica: Chic Bathroom, Rise & Grind Cafe (Fence 1)

NANDO: Fashion Store (Mirror Large)

NoStyle x Woodland: Rumasri Petbed

Pierisim: Auntie Vera Bathroom (Bathrobe), Domaine Du Clos Pt. 2|4, MCM Pt. 2|3|5, Oak House Pt. 1 (Coat Hanger), Outside Lunch, Pantry Party

Peacemaker: Arcadia, Bayside Bedroom (Dresser), Creta Indoor & Outdoor Kitchen (Urned Palm), Drapery Delights, Hickory Floorboards, Hamptons Hideaway, Hamptons Retreat, Hamptons Getaway, Hinterlands Dining (Round Dining Table), Hinterlands Living (Sectional+Chaise), Hudson Bathroom (Hamper), Kitayama Dining (Dining Chair), Volta Appliances (Under-cabinet Rangehood), Simple Siding

Plush Pixels: Shape Collection, Summer Closet

PXL: RH Baby & Child Bunk

Ravasheen: CounterFit (Mini Fridges +Trashbin), You Know the Drill (Thermastat)

RubyRed: Beaded Pendant Large

RusticSims: Kind of Modular (Books 4)

SicamCC: Life in Plastic (Vanity Chair)

Sooky88: Leaning Framed Posters – 2 Frames

Sundays: Cirrus Pt. 1|2|3, Java Pt. 1(Throw Blanket), Kediri Pt. 1 (Throw Pillows), Kedungu Pt. 1 (Throw Pillow I), Kelapa Pt. 1 (Throw Blanket), Nisaki Pt. 3, Pool Haus Pt. 1|4 (Armchair + Bar Stool), Sumba Pt. 1 (Pillow Set I + Throw Blanket), Ungasan Pt. 2 (Slippers)

Syboubou: Bamboo Foundations, Elevare (Industrial Stairs + Top)

TheClutterCat: Casita (Feeding Bowl), Fairylicious, iCare, iLove, Snuggle Set Pt. III (Wooden Candle Tray), Sunny Sundae III (Books), Welcome Home I | II

TaurusDesign: Lilith Chilling Areas Pt. 1|2

TUDS: Cross (Lamp Ceiling M), Ind 03 (2x2 Round Table), NCTR (Wallpaper Panel), Turn

Valia: Beachy, Cozy Cabin Nursery

Wondymoon: Carpinus Living Chair (website not available)

DO NOT REUPLOAD MY LOTS.

DO NOT CLAIM THEM AS YOUR OWN.

DO NOT PLACE BEHIND A PAYWALL.

DOWNLOAD (1.56 GB)

#simstorian#the sims 4#sims 4#ts4#sims 4 build#ts4 simblr#sulani#showusyourbuilds#showusyourdecor#cc build#maxis mix

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

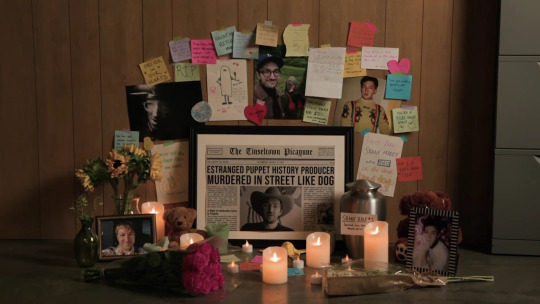

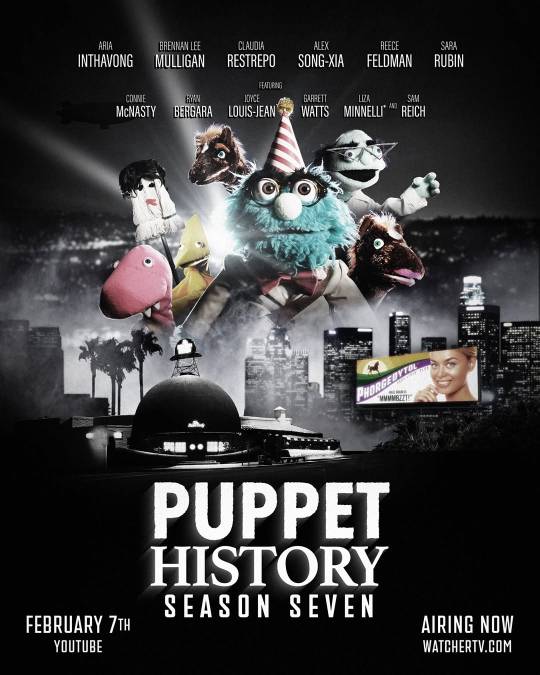

SPOILERS FOR PH 7x04

there will be MAJOR spoilers under the cut -- so DO NOT click through if you don't want to see Lore spoilers for the Watcher TV episode from Jan 31, 2025!

okay, if you're buckled up then let's crack in!

After several episodes where the Professor and Ryan have been taking Phorgedytol regularly (given to them by Elmer Walter Williams) Ryan convinces the Professor to skip their dose at the end of 7x04 and they start to remember what happened at the end of season six

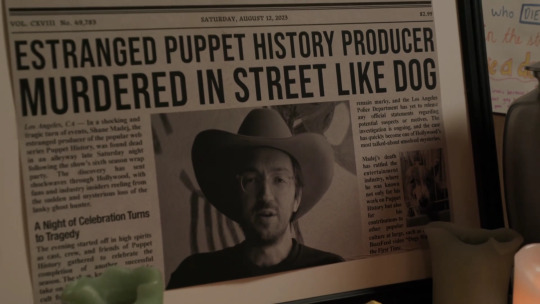

and that's when we learn the sad news that Estranged Producer Shane Madej (EPSM) died during the season six wrap party

beautiful memorial video here from @trashworldblog - RIP to a real one

now in the trailer and previous episodes we see EPSM walking down this alleyway but here we also see that he stops and turns to face his unknown assailant - so he knows who did this! (I think this will be important - more on this in a minute)

we see Ryan and the Professor both stunned at what they remember

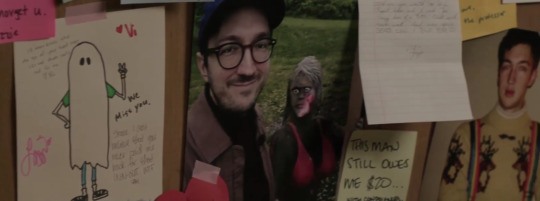

then we pan over to the memorial for Shane and there are lots of easter eggs that I wanted to point out

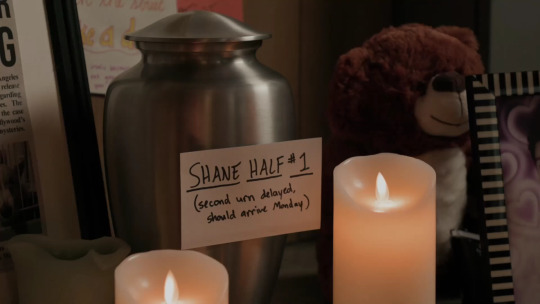

first, lmao at Shane's lanky body needing a second urn - and also Boo Buddy!

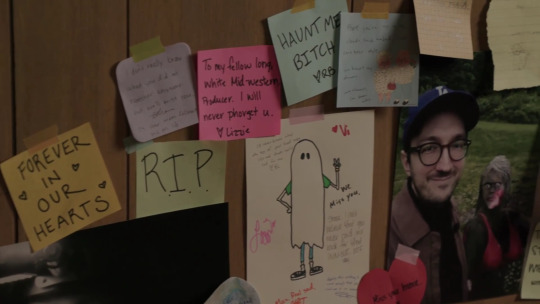

in the next shot, there's a note from someone (Shawn?) that says "I don't really know what you did at Watcher anyway but we'll miss you. PS [your mom] follows me on IG"

and Lizzie's pink note that reads "To my fellow long white Midwestern Producer. I will never phorget u. ♡ Lizzie" and she spelled forget with the "ph"

OMG! "PH" masks the true name of Phorgedytol (instead of Forget-it-all) but also PH is Puppet History!

(ahem, sorry for that random train of thought interruption - where were we?)

also scattered in the notes are at least two references to Shane owing people money with, "Shane I can't believe that you never paid me back for that In-N-Out WTF Sam" (not 100% on the name) and another that says "This man still owes me $20… with condolences"

and a note with a drawing of the Spirit Box from Ghost Files that reads "You can still star in Ghost Files if you want (but as a ghost)"

(I definitely feel like the Spirit Box will make an appearance again soon)

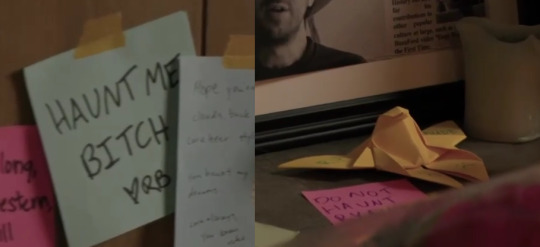

and I really wanted to point out the note that's presumably from Ryan that says "Haunt me bitch" signed with a heart (!) and the note in front of the newspaper article that reads "Do Not Haunt Ryan"

another note that could also be from Ryan reads "No for real please haunt me. I -"

(and I'm probably glad the end of this note is cut-off or I'd launch myself out a window -- if Ryan was this sad about EPSM and he made himself forget it -- I am crying in the club T_T)

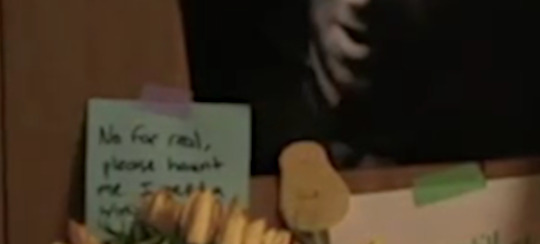

finally we get a look at this newspaper article dated Saturday, August 12, 2023, one day after the PH season six finale, which aired on August 11, 2023

I've transcribed the article below as best I could:

Estranged Puppet History Producer Murdered in the Street Like Dog Los Angeles, CA - In a shocking and tragic turn of events, Shane Madej, the estranged producer of the popular web series Puppet History, was found dead in an alleyway late Saturday night following the show's sixth season wrap party. The discovery has sent shockwaves through Hollywood, with fans and industry insiders reeling from the sudden and mysterious loss of the lanky ghost hunter. A Night of Celebration Turns to Tragedy The evening started out in high spirits as cast, crews, and friends of Puppet History gathered to celebrate the completion of another successful season --2nd column-- remain murky, and the Los Angeles Police Department has yet to release any official statements regarding potential suspects or motives. The investigation is ongoing, and the case has quickly become one of Hollywood's most talked-about unsolved mysteries. Madej's death has rattled the entertainment industry, where he was known not only for his work on Puppet History but also for his contributions to other popular culture at large, such as [hidden] BuzzFeed video "Dogs Watch Television for the First Time.

(it's so funny the article refers to him as a lanky ghost hunter and how this is the most unsolved mystery and that meme dog photo that looks like him hahahaha)

the episode ends with Ryan calling Dorothy Ruth to discover she married Elmer and the Professor wishing they could talk to EPSM, but he's dead, and Ryan says "hypothetically, what if we could"

[ROLL CREDITS]

theory: I think the Spirit Box is going to make an appearance (even better if they used Boo Buddy after all Shane has bullied him imo) to try to contact EPSM, and they'll find out he's in Purgatory with all the puppets that have been sent there and they'll finally be able to rescue them!

I do feel like Elmer has to be behind Shane's murder, even if he's not the one who pulled the trigger, but I don't quite know his motive? we've only been shown he wants to marry Dorothy Ruth but how does that involve EPSM?

and Elmer was really only dosing the Professor and Ryan with Phorgedytol, and maybe some of the other Watcher staff? but Shane's murder was in the news and being investigated by the police?? unless Elmer was really trying to cover it up by pushing the pills on all of Los Angeles and that's why they have the billboards all over town ...

fyi, there was a new billboard spotted in the PH s7 poster that Watcher put on IG yesterday that reads "Phorgedytol - Make Brain go 'MMMMBZZT!'"

maybe the PH buzzer sound?

that's all I have for now! thanks for reading and drop your thoughts and comments in the notes below!

#Watcher#Watcher TV#Puppet History#spoilers#Puppet History spoilers#omg do not read this if you haven't seen it#it will still be here waiting for you when you're ready#Estranged Producer Shane Madej#PH Lore#waywardposts#imagine writing this while Lisztomania loops in your mind hahaha good times#my ph meta

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

some times u need to let it out or it’ll consume u. i can’t keep a happy go lucky smiley tehehh face and attitude which ill prolly feel after all this emotion goes away. dude. FUCK i have to pick an urn for my daughter and i put my dog down last night. the bible says not to damn anyone bc it’s not my call blah blah blah well i hope u develop a rash in between ur toes and fingers that burns for the rest of ur life i hope ur balls swell so large they BURST i hope ur hair catches fire i hope ur toenails rips off and then maybe you’ll feel a fraction a LITTLE PIECE of what i feel u shit fuck nasty SLOB

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Truth

At six years old Ranta already understands the truth of this world and the lie of the clan. At nine, he knows how he will die. For the prompt : All of the Other Reindeer [@badthingshappenbingo]

read on AO3

or under the Read More, I'm not your boss

.

At six years old Ranta already knows the truth of this world : it isn’t the strong that survive and live well, but the ones lucky enough to be born up high.

Dad had the pitiful technique of a man from the lower branch and died pitifully before Ranta could even remember him. Mom broke her neck falling down the stairs going up to the compound, and it was another servant that found her body.

Ranta’s hands were too small and clumsy at the time to properly hold the chopsticks and put her bones in the urn. He doesn’t remember where her ashes are now.

Ranta is six and carrying trays and laundry to the main house, watching the lucky ones parade around in rich clothes that don’t fray and don’t look or feel rough at all.

Only Zen’in are sorcerers, and only sorcerers are human, and only the strong deserve to live – and yet Ranta barely feels human and still thinks that he doesn’t want to die.

Ranta’s technique is weak and useless, he knows this because dad had the same and still died, and because branch kids are nothing but dog meat sacrificed to keep the main line alive.

Only the Ten Shadows matters, and everyone else lives and dies only for his sake.

Ranta is six and knows he will die like dad, like mom, pathetic and worthless. He has no reason to expect anything else.

He is six when the head of Hei comes to watch a demonstration of the lower branch’s techniques, barely paying any attention as he drinks his sake. Jin’ichi-sama is only here for the sake of tradition, for the sake of pretending it is strength that matters and not only how close to power you are born. Everyone knows it.

Everyone knows it, and that’s why no one expects it when he calls Ranta up to him and says : “You have potential.”

Ranta’s nose is bleeding from overexertion, because he is weak and lacks training, and he can’t tell if his face flushes and his sight blurs from effort, or from the awe of seeing Jin’ichi-sama look down upon him in approval, and feeling his large hand envelop Ranta’s head like he imagines dad would have.

After this, Ranta is moved closer to the main house, stops carrying trays and laundry that aren’t exclusively Jin’ichi-sama’s, starts wearing clothes that feel soft against his skin. He trains under Jin’ichi-sama when he isn’t serving him, and each little word of encouragement, each warm touch on his shoulder or his head feels like one of the blessings he wasn’t born with.

Still, he doesn’t forget the truth of this world : the lucky ones are the ones who get to survive, and Jin’ichi-sama is simply sharing his own luck with Ranta now.

Without him, Ranta would be nothing.

It isn’t the strong that live well, he knew and still knows, and will forever know. If it was, the ghost he first heard of back in the lowest house wouldn’t be a curse in and of himself, and Jin’ichi-sama wouldn’t have ever felt the need to set his eyes on Ranta.

The ghost of the main family is a child two years older, who stares at Ranta with the anger of a vengeful spirit, and stands lower than Ranta ever used to, even though he lives in the main house.

He is strong, too. Jin’ichi-sama trains Ranta to support him, Ranta keeping the target immobile while Jin’ichi-sama crushes it at full power, the perfect helping hand to a technique that lacks in finesse and accuracy (Jin’ichi-sama’s words) – Toji needs none of this. Toji is fast and strong, accurate and powerful, all on his own.

Toji has no cursed energy.

Ranta thought himself worthless, and yet next to Toji his existence means the world to the clan, and to Jin’ichi-sama. Toji isn’t really a human, a person, a son. Toji is nothing except strong.

And yet, and yet, the lie of the Zen’in keeps on going that the only thing that matters is strength, and that is why the strongest sorcerer is the head of Hei, and the Ten Shadows will always be the head of the clan.

It isn’t that Ranta feels pity for Toji, it isn’t, either, that he hates him as much as Toji resents him. Something just feels wrong, is all. Or maybe not wrong, but odd. Uneven.

Ranta owes his current life to Toji’s curse, but he cannot be grateful. Cannot show any kindness, doesn’t have any reason to either because Toji is mean, to everyone and especially to Ranta, but he is also the only kid around the same age who isn’t one of Naobito’s horrible sons and it’s not that Ranta is lonely, he isn’t, cannot be when Jin’ichi-sama is so kind to him, but… but…

He doesn’t want to lose his place in the world.

It’s all that matters, this, and Jin’ichi-sama looking at him like dad would have. Ranta will do anything for this.

When Ranta is nine years old, Jin’ichi-sama’s wife dies.

He has never met her, she kept herself locked inside her room ever since giving birth to a defective child, but he knows Jin’ichi-sama loved her, or he would have divorced her back then.

Jin’ichi-sama doesn’t come to train the next day, doesn’t call Ranta to serve him either.

Ranta goes anyway.

He couldn’t get mom’s bones into the urn properly when she died, forgot where her ashes are. He doesn’t want Jin’ichi-sama to feel as lonely as he did back then.

When he reaches the main house from the courtyard, Toji is standing outside, glaring at Ranta like he expected him, like he’s been watching Ranta cross the garden from the start and Ranta just didn’t notice it. Maybe that’s the case.

“Go away,” Toji says. “He won’t train you today,” he says. Like Ranta is a stupid child who doesn’t even understand this much.

“I’m not here to train.”

“Go away,” Toji repeats. “We’re,” he catches himself, “he’s in mourning. You’re not family, so don’t come in.”

It’s a lie. They’re all Zen’in, even Toji, even someone who isn’t even a person. For some reason, Ranta doesn’t want to let him be mean today. Doesn’t want to hear those specific words.

“I want to present my condolences. I’m not leaving.”

He takes a step forward. So does Toji, grabbing Ranta’s collar and dragging him back, before throwing him onto the ground.

Ranta barely has the time to understand what happened before Toji punches him. And then he doesn’t have the time to understand anything anymore, except that it hurts and Toji is angry and shouting and straddling Ranta to hit him more.

“I told you” hit “to go” hit “away.”

Hit.

“No one wants you here !” Toji shouts at one point. “It’s all your fault ! You ruined everything !”

Ranta can’t even raise his hands to defend himself, much less speak up. He just lies here, taking in the punches and the words, and the emotion in Toji’s eyes that he recognizes for the first time.

It’s fear.

It’s always been fear.

The hail of hits stops as Toji is dragged up to his feet, and Ranta watches as Toji tries to explain himself and begs for his father to forgive him, panicked and hurried and so unlike himself.

It doesn’t stop the heavy blow he receives though, hard enough to make him keel over and throw up.

“I have no son,” Jin’ichi-san says in a cold, dead voice Ranta never heard from him before.

It scares him.

It scares him, too, when he doesn’t see Toji for a week after, when Jin’ichi-san doesn’t say where he took him.

It scares him when he finally understands, watching the doors to the underground training area open and feeling none of the cursed energy that should emanate from the numerous curses held within it.

Watching Toji slowly limp his way out, covered in blood and gaping wounds, with eyes so empty Ranta feels himself lose his footing and fall somewhere he doesn’t belong anymore.

At nine years old, Ranta understands the truths of this world : it isn’t the strong that get to live well, but the ones that are born lucky. Toji is the strongest of the Zen’in, and one day he will take revenge on them all, and he will kill them all with no struggle and no qualms. And when he takes Ranta’s life, then…

Ranta thinks he will deserve it.

#bad things happen bingo#jujutsu kaisen#yumi writes#zenin ranta#fushiguro toji#zenin jinichi#child abuse#jinichi is toji's dad in this fic#bc im a daddy jinichi truther#(its bc i dont read the tankobon)#(so i didnt know about the family tree extra)#anyway ranta ! i love this guy#want to put him in a centrifuge#and analyze what comes out with a microscope#guy who knows everything is bad#and refuses to do anything about it#he will enforce systems of domination#but he'll be really nice about it :)#lotsa cool things on the card btw !!#but the thumbscrew in the middle is so evil lmao

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Posting my current list of things i wanna draw cause honestly, id much rather see someone elses take on a lot of them.

Most of these are labeled under "degenerate art ideas" so take from that what you will.

Please feel free to use any one of these.

-----

- The Kiss from fallout. If you know you know. Bane and bhaal with a dead durge and gortash.

-Comic: Astarion in trouble and drizzt comes out of nowhere all heroic and saves him and hes all doe eyed n shit.

-Halsin and mr meadhoney. "Do you have a particular fondness for large and...heavily armed men, mr. Meadhoney?"

-Lucretious the necromancer and astarion dancing the tango together with the skellies in the back playing music."The dead are always such superb dancers."

-Comic: Lucretious topping astarion, bent over the stages edge. "What if we put you in my show darling. Im sure we could find something for a star like you...something youd love as much as the crowd."

"Youd make a spectacle of me?"

"In front of THOUSANDS who come just to see the most perfect beauty in all of the planes."

"Oh yes i quite like the thought of that."

-Comic: "Orin: you suck up the tyrants vapors like a babe sucks milk."

"Durge: tch fuckin yeah i do."

"Astarion: D:<!!?"

"Orin: *quinten terantino scowl that she does*"

-Vellioth as the "i yearn for the urn" tiktok

- astarion amputee doodles (thank you godey for that idea)

-3 musketeers quote "i love that in a man." "What. Passion?" "Violence" but ghoap or durge. Maybe make a version of both?

-when (doodly dude) hit me real hard that one night and my jaw rattled in my skull all nasty, but make it durgestarion hehehehehehe

-Astarion licking blood from durge in one of the pools of blood (idea from mignon scene)

-Durgetash comic of demon slayer masochism abridged thing with the lady man demon

- bg3 crew bein a bunch of rly cute parrots doin dumb cute things.

-same idea but theyre all shoebill storks.

-comic: "Mighty sanctum" bit, then durge pulls astarion into his lap and kisses him. "Fairly certain you would castrate me if i tried to fuck you right here like i want...im still not sure if thats a deterrent or temptation" but ya know...better written.

"bloody degenerate...unhand me."

"Let go of my neck then."

"No"

"Well then...")

-Mungojerrie from cats and astarion both comolimenting each others pearls and casually holding something they swiped from the other. Riumpleteaser and durge are snickering and sharing a look, while RT has swiped something of durges, durge is pulling out his/her dagger

- Durge/Tav painting astarion in gold, and feeding him blood in a hedonism date night. he thinks the gold paint is just for tav. But he keeps saying "i just want you to see yourself as i see you." And stuch things.

He leads him to a giant ass mirror and lo and behold, there he is. In the flesh. The colors arent there of course. Hes looks like a statue, but its still...its more than the statue, its more than a portrait.

-Lyrical comic of durgetash ritual by ghost

-comic: Astarion is walking with the gang. He looks up to see something and narrows his eyes. He suddenly bursts into bats, flies up onto the space he was trying to peer at and reappears in a panic. Somethin like....

"I was eight bats...how...fuck...gods how am i supposed to even process that!?

Astarion are you alri

"I WAS IN EIGHT FUCKING PLACES AT ONCE TAV I AM NOT ALRIGHT"

-comic- Volothamp talking to tav about a rat exodus from "a mysterious "red castle" " where their bretheren kept going missing. So they gave up the territory and moved to a "red cave" just beneath it, where blood flows even more freely.

Astsrion recognizes the palace, and remembers a time where rats were in such short supply that cazador had simply switched to insects for a while. Well with astarion he had, the rest had been treated to cats and dogs, in order to lessen the threat against the local rat population. Durge in the meantime, has an odd memory about commanding rats to find reconnisance if they wish to find safety with (fuzzy writing that doesnt quite translate to words)

-Astarions ascension but its happy with evil hugs.

-Durge reacting to the gnoll birth holy hells that was funny.

-Durge eviscerating astarion while he arches off the ground as if in ecstacy rather than pain. Theyre both laughing in wild, crying hysterics and theres those timasks spores everywhere.

-Comic: A -Astarion in the mirror frowning and looking distressed, even a little pissed in a mini panel, as he pinches a small amount of belly fat. Hes a very healthy weight but like 200 years o trauma dawg. Next pannel he looks thoughtful (considering that hes never had enough to eat before to warrant gaining rather than steadily losing weight), third panel he looks up in a catlike manner and fingertip taps his stomach near his hip. Very silly smug cat face meme feels here

-Chaste kiss canon durgestarion/tash vs nasty canon durgestarion/tash

-Comic of vellioth uncovering mummystarion from crypt.

-Comic of astarion fucking posessed n bound durge in the shar library.

-An archer in general doing leg archery. Maybe two goofballs doin it at each other with silly faces. I can see any combo of minsc and lazel and astarion doing this weirdly enough.

-spit/ blood exchange between s/a astarions.

-That moment when astarion is blissed out in the sauce under durge in the grove. Maybe a pov where theres drops of blood mid fall, and theres two hands smearing it all over his chest.

-A astarion sitting on bhaals altar while durge and gortash dogfight.

-Gortash with his hand inside a lasceration in durges belly, squeezing himself off all slowlike inside durge. bloody handprints everywhere, though some have turned to black sooted handprints. Theyre kissing all disgustin

-Slayer and a predator Shilouetted gwtw style

-Astarion getting railed by a Predator.

-Lazel getting railed by a Predator.

-Honestly just put everyone in every fandom with a predator at some point like fu c ks sake

-Comic of the superimposed cazador murder/thunderstorm blood frenzy xex scene from that one fic i never finished

-The king E x Ragnar bath scene but nasty. (Also durgetash?)

-Astarion with floorlength hair and dripping with pearls, looking a little emaciated, or perhaps just extra slender themes to the art

Two smaller panels where vellioth h it away and carefully styles it while figaros corpse lays in the corner. Vellioth should look younger but less pretty.

-Durge slips his hands into astarions back pockets (in this comic he has invented ass pockets) "butt"

He goes "no, butt." And walks away. Durge looks down at his hands that are still right there where his butt was. And he squeezes the air with a smile

#thats alotta brainrot#astarion#durgetash#enver gortash#tavstarion#durgestarion#art#art ideas#blorbo#plot bunny#bg3#baldur's gate 3

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book the Second—The Golden Thread

[X] Chapter IX. The Gorgon's Head

It was a heavy mass of building, that chateau of Monsieur the Marquis, with a large stone courtyard before it, and two stone sweeps of staircase meeting in a stone terrace before the principal door. A stony business altogether, with heavy stone balustrades, and stone urns, and stone flowers, and stone faces of men, and stone heads of lions, in all directions. As if the Gorgon’s head had surveyed it, when it was finished, two centuries ago.

Up the broad flight of shallow steps, Monsieur the Marquis, flambeau preceded, went from his carriage, sufficiently disturbing the darkness to elicit loud remonstrance from an owl in the roof of the great pile of stable building away among the trees. All else was so quiet, that the flambeau carried up the steps, and the other flambeau held at the great door, burnt as if they were in a close room of state, instead of being in the open night-air. Other sound than the owl’s voice there was none, save the falling of a fountain into its stone basin; for, it was one of those dark nights that hold their breath by the hour together, and then heave a long low sigh, and hold their breath again.

The great door clanged behind him, and Monsieur the Marquis crossed a hall grim with certain old boar-spears, swords, and knives of the chase; grimmer with certain heavy riding-rods and riding-whips, of which many a peasant, gone to his benefactor Death, had felt the weight when his lord was angry.

Avoiding the larger rooms, which were dark and made fast for the night, Monsieur the Marquis, with his flambeau-bearer going on before, went up the staircase to a door in a corridor. This thrown open, admitted him to his own private apartment of three rooms: his bed-chamber and two others. High vaulted rooms with cool uncarpeted floors, great dogs upon the hearths for the burning of wood in winter time, and all luxuries befitting the state of a marquis in a luxurious age and country. The fashion of the last Louis but one, of the line that was never to break—the fourteenth Louis—was conspicuous in their rich furniture; but, it was diversified by many objects that were illustrations of old pages in the history of France.

A supper-table was laid for two, in the third of the rooms; a round room, in one of the chateau’s four extinguisher-topped towers. A small lofty room, with its window wide open, and the wooden jalousie-blinds closed, so that the dark night only showed in slight horizontal lines of black, alternating with their broad lines of stone colour.

“My nephew,” said the Marquis, glancing at the supper preparation; “they said he was not arrived.”

Nor was he; but, he had been expected with Monseigneur.

“Ah! It is not probable he will arrive to-night; nevertheless, leave the table as it is. I shall be ready in a quarter of an hour.”

In a quarter of an hour Monseigneur was ready, and sat down alone to his sumptuous and choice supper. His chair was opposite to the window, and he had taken his soup, and was raising his glass of Bordeaux to his lips, when he put it down.

“What is that?” he calmly asked, looking with attention at the horizontal lines of black and stone colour.

“Monseigneur? That?”

“Outside the blinds. Open the blinds.”

It was done.

“Well?”

“Monseigneur, it is nothing. The trees and the night are all that are here.”

The servant who spoke, had thrown the blinds wide, had looked out into the vacant darkness, and stood with that blank behind him, looking round for instructions.

“Good,” said the imperturbable master. “Close them again.”

That was done too, and the Marquis went on with his supper. He was half way through it, when he again stopped with his glass in his hand, hearing the sound of wheels. It came on briskly, and came up to the front of the chateau.

“Ask who is arrived.”

It was the nephew of Monseigneur. He had been some few leagues behind Monseigneur, early in the afternoon. He had diminished the distance rapidly, but not so rapidly as to come up with Monseigneur on the road. He had heard of Monseigneur, at the posting-houses, as being before him.

He was to be told (said Monseigneur) that supper awaited him then and there, and that he was prayed to come to it. In a little while he came. He had been known in England as Charles Darnay.

Monseigneur received him in a courtly manner, but they did not shake hands.

“You left Paris yesterday, sir?” he said to Monseigneur, as he took his seat at table.

“Yesterday. And you?”

“I come direct.”

“From London?”

“Yes.”

“You have been a long time coming,” said the Marquis, with a smile.

“On the contrary; I come direct.”

“Pardon me! I mean, not a long time on the journey; a long time intending the journey.”

“I have been detained by”—the nephew stopped a moment in his answer—“various business.”

“Without doubt,” said the polished uncle.

So long as a servant was present, no other words passed between them. When coffee had been served and they were alone together, the nephew, looking at the uncle and meeting the eyes of the face that was like a fine mask, opened a conversation.

“I have come back, sir, as you anticipate, pursuing the object that took me away. It carried me into great and unexpected peril; but it is a sacred object, and if it had carried me to death I hope it would have sustained me.”

“Not to death,” said the uncle; “it is not necessary to say, to death.”

“I doubt, sir,” returned the nephew, “whether, if it had carried me to the utmost brink of death, you would have cared to stop me there.”

The deepened marks in the nose, and the lengthening of the fine straight lines in the cruel face, looked ominous as to that; the uncle made a graceful gesture of protest, which was so clearly a slight form of good breeding that it was not reassuring.

“Indeed, sir,” pursued the nephew, “for anything I know, you may have expressly worked to give a more suspicious appearance to the suspicious circumstances that surrounded me.”

“No, no, no,” said the uncle, pleasantly.

“But, however that may be,” resumed the nephew, glancing at him with deep distrust, “I know that your diplomacy would stop me by any means, and would know no scruple as to means.”

“My friend, I told you so,” said the uncle, with a fine pulsation in the two marks. “Do me the favour to recall that I told you so, long ago.”

“I recall it.”

“Thank you,” said the Marquis—very sweetly indeed.

His tone lingered in the air, almost like the tone of a musical instrument.

“In effect, sir,” pursued the nephew, “I believe it to be at once your bad fortune, and my good fortune, that has kept me out of a prison in France here.”

“I do not quite understand,” returned the uncle, sipping his coffee. “Dare I ask you to explain?”

“I believe that if you were not in disgrace with the Court, and had not been overshadowed by that cloud for years past, a letter de cachet would have sent me to some fortress indefinitely.”

“It is possible,” said the uncle, with great calmness. ��For the honour of the family, I could even resolve to incommode you to that extent. Pray excuse me!”

“I perceive that, happily for me, the Reception of the day before yesterday was, as usual, a cold one,” observed the nephew.

“I would not say happily, my friend,” returned the uncle, with refined politeness; “I would not be sure of that. A good opportunity for consideration, surrounded by the advantages of solitude, might influence your destiny to far greater advantage than you influence it for yourself. But it is useless to discuss the question. I am, as you say, at a disadvantage. These little instruments of correction, these gentle aids to the power and honour of families, these slight favours that might so incommode you, are only to be obtained now by interest and importunity. They are sought by so many, and they are granted (comparatively) to so few! It used not to be so, but France in all such things is changed for the worse. Our not remote ancestors held the right of life and death over the surrounding vulgar. From this room, many such dogs have been taken out to be hanged; in the next room (my bedroom), one fellow, to our knowledge, was poniarded on the spot for professing some insolent delicacy respecting his daughter—his daughter? We have lost many privileges; a new philosophy has become the mode; and the assertion of our station, in these days, might (I do not go so far as to say would, but might) cause us real inconvenience. All very bad, very bad!”

The Marquis took a gentle little pinch of snuff, and shook his head; as elegantly despondent as he could becomingly be of a country still containing himself, that great means of regeneration.

“We have so asserted our station, both in the old time and in the modern time also,” said the nephew, gloomily, “that I believe our name to be more detested than any name in France.”

“Let us hope so,” said the uncle. “Detestation of the high is the involuntary homage of the low.”

“There is not,” pursued the nephew, in his former tone, “a face I can look at, in all this country round about us, which looks at me with any deference on it but the dark deference of fear and slavery.”

“A compliment,” said the Marquis, “to the grandeur of the family, merited by the manner in which the family has sustained its grandeur. Hah!” And he took another gentle little pinch of snuff, and lightly crossed his legs.

But, when his nephew, leaning an elbow on the table, covered his eyes thoughtfully and dejectedly with his hand, the fine mask looked at him sideways with a stronger concentration of keenness, closeness, and dislike, than was comportable with its wearer’s assumption of indifference.

“Repression is the only lasting philosophy. The dark deference of fear and slavery, my friend,” observed the Marquis, “will keep the dogs obedient to the whip, as long as this roof,” looking up to it, “shuts out the sky.”

That might not be so long as the Marquis supposed. If a picture of the chateau as it was to be a very few years hence, and of fifty like it as they too were to be a very few years hence, could have been shown to him that night, he might have been at a loss to claim his own from the ghastly, fire-charred, plunder-wrecked rains. As for the roof he vaunted, he might have found that shutting out the sky in a new way—to wit, for ever, from the eyes of the bodies into which its lead was fired, out of the barrels of a hundred thousand muskets.

“Meanwhile,” said the Marquis, “I will preserve the honour and repose of the family, if you will not. But you must be fatigued. Shall we terminate our conference for the night?”

“A moment more.”

“An hour, if you please.”

“Sir,” said the nephew, “we have done wrong, and are reaping the fruits of wrong.”

“We have done wrong?” repeated the Marquis, with an inquiring smile, and delicately pointing, first to his nephew, then to himself.

“Our family; our honourable family, whose honour is of so much account to both of us, in such different ways. Even in my father’s time, we did a world of wrong, injuring every human creature who came between us and our pleasure, whatever it was. Why need I speak of my father’s time, when it is equally yours? Can I separate my father’s twin-brother, joint inheritor, and next successor, from himself?”

“Death has done that!” said the Marquis.

“And has left me,” answered the nephew, “bound to a system that is frightful to me, responsible for it, but powerless in it; seeking to execute the last request of my dear mother’s lips, and obey the last look of my dear mother’s eyes, which implored me to have mercy and to redress; and tortured by seeking assistance and power in vain.”

“Seeking them from me, my nephew,” said the Marquis, touching him on the breast with his forefinger—they were now standing by the hearth—“you will for ever seek them in vain, be assured.”

Every fine straight line in the clear whiteness of his face, was cruelly, craftily, and closely compressed, while he stood looking quietly at his nephew, with his snuff-box in his hand. Once again he touched him on the breast, as though his finger were the fine point of a small sword, with which, in delicate finesse, he ran him through the body, and said,

“My friend, I will die, perpetuating the system under which I have lived.”

When he had said it, he took a culminating pinch of snuff, and put his box in his pocket.

“Better to be a rational creature,” he added then, after ringing a small bell on the table, “and accept your natural destiny. But you are lost, Monsieur Charles, I see.”

“This property and France are lost to me,” said the nephew, sadly; “I renounce them.”

“Are they both yours to renounce? France may be, but is the property? It is scarcely worth mentioning; but, is it yet?”

“I had no intention, in the words I used, to claim it yet. If it passed to me from you, to-morrow—”

“Which I have the vanity to hope is not probable.”

“—or twenty years hence—”

“You do me too much honour,” said the Marquis; “still, I prefer that supposition.”

“—I would abandon it, and live otherwise and elsewhere. It is little to relinquish. What is it but a wilderness of misery and ruin!”

“Hah!” said the Marquis, glancing round the luxurious room.

“To the eye it is fair enough, here; but seen in its integrity, under the sky, and by the daylight, it is a crumbling tower of waste, mismanagement, extortion, debt, mortgage, oppression, hunger, nakedness, and suffering.”

“Hah!” said the Marquis again, in a well-satisfied manner.

“If it ever becomes mine, it shall be put into some hands better qualified to free it slowly (if such a thing is possible) from the weight that drags it down, so that the miserable people who cannot leave it and who have been long wrung to the last point of endurance, may, in another generation, suffer less; but it is not for me. There is a curse on it, and on all this land.”

“And you?” said the uncle. “Forgive my curiosity; do you, under your new philosophy, graciously intend to live?”

“I must do, to live, what others of my countrymen, even with nobility at their backs, may have to do some day—work.”

“In England, for example?”

“Yes. The family honour, sir, is safe from me in this country. The family name can suffer from me in no other, for I bear it in no other.”

The ringing of the bell had caused the adjoining bed-chamber to be lighted. It now shone brightly, through the door of communication. The Marquis looked that way, and listened for the retreating step of his valet.

“England is very attractive to you, seeing how indifferently you have prospered there,” he observed then, turning his calm face to his nephew with a smile.

“I have already said, that for my prospering there, I am sensible I may be indebted to you, sir. For the rest, it is my Refuge.”

“They say, those boastful English, that it is the Refuge of many. You know a compatriot who has found a Refuge there? A Doctor?”

“Yes.”

“With a daughter?”

“Yes.”

“Yes,” said the Marquis. “You are fatigued. Good night!”

As he bent his head in his most courtly manner, there was a secrecy in his smiling face, and he conveyed an air of mystery to those words, which struck the eyes and ears of his nephew forcibly. At the same time, the thin straight lines of the setting of the eyes, and the thin straight lips, and the markings in the nose, curved with a sarcasm that looked handsomely diabolic.

“Yes,” repeated the Marquis. “A Doctor with a daughter. Yes. So commences the new philosophy! You are fatigued. Good night!”

It would have been of as much avail to interrogate any stone face outside the chateau as to interrogate that face of his. The nephew looked at him, in vain, in passing on to the door.

“Good night!” said the uncle. “I look to the pleasure of seeing you again in the morning. Good repose! Light Monsieur my nephew to his chamber there!—And burn Monsieur my nephew in his bed, if you will,” he added to himself, before he rang his little bell again, and summoned his valet to his own bedroom.

The valet come and gone, Monsieur the Marquis walked to and fro in his loose chamber-robe, to prepare himself gently for sleep, that hot still night. Rustling about the room, his softly-slippered feet making no noise on the floor, he moved like a refined tiger:—looked like some enchanted marquis of the impenitently wicked sort, in story, whose periodical change into tiger form was either just going off, or just coming on.

He moved from end to end of his voluptuous bedroom, looking again at the scraps of the day’s journey that came unbidden into his mind; the slow toil up the hill at sunset, the setting sun, the descent, the mill, the prison on the crag, the little village in the hollow, the peasants at the fountain, and the mender of roads with his blue cap pointing out the chain under the carriage. That fountain suggested the Paris fountain, the little bundle lying on the step, the women bending over it, and the tall man with his arms up, crying, “Dead!”

“I am cool now,” said Monsieur the Marquis, “and may go to bed.”

So, leaving only one light burning on the large hearth, he let his thin gauze curtains fall around him, and heard the night break its silence with a long sigh as he composed himself to sleep.

The stone faces on the outer walls stared blindly at the black night for three heavy hours; for three heavy hours, the horses in the stables rattled at their racks, the dogs barked, and the owl made a noise with very little resemblance in it to the noise conventionally assigned to the owl by men-poets. But it is the obstinate custom of such creatures hardly ever to say what is set down for them.

For three heavy hours, the stone faces of the chateau, lion and human, stared blindly at the night. Dead darkness lay on all the landscape, dead darkness added its own hush to the hushing dust on all the roads. The burial-place had got to the pass that its little heaps of poor grass were undistinguishable from one another; the figure on the Cross might have come down, for anything that could be seen of it. In the village, taxers and taxed were fast asleep. Dreaming, perhaps, of banquets, as the starved usually do, and of ease and rest, as the driven slave and the yoked ox may, its lean inhabitants slept soundly, and were fed and freed.

The fountain in the village flowed unseen and unheard, and the fountain at the chateau dropped unseen and unheard—both melting away, like the minutes that were falling from the spring of Time—through three dark hours. Then, the grey water of both began to be ghostly in the light, and the eyes of the stone faces of the chateau were opened.

Lighter and lighter, until at last the sun touched the tops of the still trees, and poured its radiance over the hill. In the glow, the water of the chateau fountain seemed to turn to blood, and the stone faces crimsoned. The carol of the birds was loud and high, and, on the weather-beaten sill of the great window of the bed-chamber of Monsieur the Marquis, one little bird sang its sweetest song with all its might. At this, the nearest stone face seemed to stare amazed, and, with open mouth and dropped under-jaw, looked awe-stricken.

Now, the sun was full up, and movement began in the village. Casement windows opened, crazy doors were unbarred, and people came forth shivering—chilled, as yet, by the new sweet air. Then began the rarely lightened toil of the day among the village population. Some, to the fountain; some, to the fields; men and women here, to dig and delve; men and women there, to see to the poor live stock, and lead the bony cows out, to such pasture as could be found by the roadside. In the church and at the Cross, a kneeling figure or two; attendant on the latter prayers, the led cow, trying for a breakfast among the weeds at its foot.

The chateau awoke later, as became its quality, but awoke gradually and surely. First, the lonely boar-spears and knives of the chase had been reddened as of old; then, had gleamed trenchant in the morning sunshine; now, doors and windows were thrown open, horses in their stables looked round over their shoulders at the light and freshness pouring in at doorways, leaves sparkled and rustled at iron-grated windows, dogs pulled hard at their chains, and reared impatient to be loosed.

All these trivial incidents belonged to the routine of life, and the return of morning. Surely, not so the ringing of the great bell of the chateau, nor the running up and down the stairs; nor the hurried figures on the terrace; nor the booting and tramping here and there and everywhere, nor the quick saddling of horses and riding away?

What winds conveyed this hurry to the grizzled mender of roads, already at work on the hill-top beyond the village, with his day’s dinner (not much to carry) lying in a bundle that it was worth no crow’s while to peck at, on a heap of stones? Had the birds, carrying some grains of it to a distance, dropped one over him as they sow chance seeds? Whether or no, the mender of roads ran, on the sultry morning, as if for his life, down the hill, knee-high in dust, and never stopped till he got to the fountain.

All the people of the village were at the fountain, standing about in their depressed manner, and whispering low, but showing no other emotions than grim curiosity and surprise. The led cows, hastily brought in and tethered to anything that would hold them, were looking stupidly on, or lying down chewing the cud of nothing particularly repaying their trouble, which they had picked up in their interrupted saunter. Some of the people of the chateau, and some of those of the posting-house, and all the taxing authorities, were armed more or less, and were crowded on the other side of the little street in a purposeless way, that was highly fraught with nothing. Already, the mender of roads had penetrated into the midst of a group of fifty particular friends, and was smiting himself in the breast with his blue cap. What did all this portend, and what portended the swift hoisting-up of Monsieur Gabelle behind a servant on horseback, and the conveying away of the said Gabelle (double-laden though the horse was), at a gallop, like a new version of the German ballad of Leonora?

It portended that there was one stone face too many, up at the chateau.

The Gorgon had surveyed the building again in the night, and had added the one stone face wanting; the stone face for which it had waited through about two hundred years.

It lay back on the pillow of Monsieur the Marquis. It was like a fine mask, suddenly startled, made angry, and petrified. Driven home into the heart of the stone figure attached to it, was a knife. Round its hilt was a frill of paper, on which was scrawled:

“Drive him fast to his tomb. This, from Jacques.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Antique Ormolu Bronze Porcelain Urn Vase LARGE 19th C French Sevres Hunting Dogs EBAY Light of the World Lamps

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

DRAGON AGE VERSE

BEGINNINGS

Artemis first joined the Dalish when fleeing from slavery in Tevinter as a child. Alone, ragged, and found near the Sunless Lands of the Korcari Wilds, the Clan Mihris took her in as one of their own. Strong magic prevailed through Artemis's veins unlike a magnitude that of which the young Keeper Virhen had seen before. It initially sparked fear of being unable to control it, and for a while, Keeper Virhen and Hahren Merudios elected to train Artemis in the skills of a hunter and ranger instead.

Later that year during the Arlathvhen (a meeting between Dalish clans all over Thedas to keep and exchange lore that they may have rediscovered) Keeper Virhen shared her concerns of Artemis's unusual magical potency. Upon advice from the other Keepers, Keeper Virhen enlisted Artemis as her First, an apprentice mage designated to study Elven history and magic in an attempt to keep the lore alive and maintain magic in a growing trend of less magically-enabled Dalish.

DRAGON AGE: ORIGINS

In 9:30 Dragon the Fifth Blight began. Darkspawn quickly surged in the Korcari Wilds as well as the Hinterlands. Clan Mihris, freshly travelled from the Brecelian Forest, camped a small distance from the settlement of Sothmere to allow the Halla to graze. In the night, Sothmere comes under attack by the Darkspawn, and Artemis spots the flames in the distance.

Against the advice of her Keeper Artemis goes to Sothmere to help the local villagers. While she successfully defeats the number of Darkspawn the villagers believe her to have been the one to cause the incursion, citing the Dalish presence as having attracted unholy wild creatures. The villagers become irate and violent toward Artemis--unaccustomed and having never been subject to such hostility from humans, Artemis becomes indignant, only adding fuel to the fire.

Keeper Virhen arrives to retrieve Artemis only to find that battle had erupted between her and the villagers. Nothing was left of the humans save for charred remains, much like a large part of the village. It is now that Templars from the nearby Circle arrive upon the scene and immediately begin to apprehend the two elves. Keeper Virhen begins to explain in earnest the entire misunderstanding and is struck dead by a Templar.

Artemis once again erupts into a furious magical cyclone at the sight of her Keeper killed while trying to defend her. The Templars only just capture the mage and cite her as a high risk for turning into an abomination with the lack of control that she displays--not to mention the crimes committed. Artemis is taken into a caravan and escorted to Denerim for judgement.

Duncan intercepts the caravan and conscripts Artemis into the Grey Wardens shortly afterwards. She completes the Joining with the Hero of Ferelden and aids them with Alistair at the Battle of Ostagar.

Artemis remains with the Hero of Ferelden's party throughout the events of the Fifth Blight.

Choices/approval:

Approves recruiting Sten, Dog, Wynne, Morrigan, Shale, Zevran

Disapproves recruiting Leliana, Oghren

Slightly disapproves helping Redcliffe Village

Save both Connor and Isolde

Leave the Urn alone

Save the Mages

Sides with the elves, approves making peace between the werewolves and the elves in the Brecilian Forest

Supports Bhelen

Disapproves helping Burkle open the Chantry

Disapproves Anora ruling alone, approve Anora and Alistair, approve Anora and the Warden, disapprove Alistair ruling alone

Greatly approves killing Loghain

Greatly disapproves recruiting Loghain

Disapproves of the Dark Ritual, chooses to complete the Final Sacrifice herself as a Grey Warden

AFTERMATH

Artemis will sacrifice herself during the final battle against the Archdemon. Instead of remaining dead, however, the process only nullifies the Darkspawn blood inside of her and removes all of her Grey Warden abilities. She will wake back up at the end of the battle in a very confused state.

In the coming months, Artemis is removed from the Grey Wardens once it is established that the Darkspawn blood inside of her has completely dissolved. Although they do attempt to go through the Joining with her once more, it has little to no effect upon her for an unknown reason.

Artemis later finds Grand Enchanter Fiona upon being informed that she was the first and only Grey Warden to be discharged from service due to the same circumstances. Artemis and Fiona disagree upon whether or not to research this anomaly; Fiona would rather remain with her second lease upon life while Artemis is mystified and upset with the sudden lack of purpose in her life.

DRAGON AGE: II

Artemis may be interacted with in Kirkwall only in passing, although she does join the mage uprising in the mage/templar conflict. She will provide a sidequest for Hawke's party to scour Ferelden for Darkspawn blood samples given that Hawke does not offend her during dialogue.

When the mage-templar war fully erupts in 9:37 Dragon, Artemis can be found fighting alongside the rebel mages.

DRAGON AGE: INQUISITION

Artemis ultimately fled from Kirkwall and Ferelden due to the fighting happening. While first dedicated to the cause of the rebel mages, she took priority in her research upon her lost Grey Warden status and moved west to Orlais. Though the civil war had erupted and politics were as tense as ever, Artemis successfully established herself in Val Royeaux as a source of magical knowledge.

Artemis's elven status made things quite difficult. The disparity between the elves and the Orlesian nobility was far and wide. In an effort to climb the ranks, Artemis sought out a position in Empress Celene's court, but found no room for an elf in the Grand Game. Shortly after this, Briala instead invites her to become a part of her extensive spy network throughout the Orlesian Empire. Artemis agrees to this and begins work as an elven servant at Halamshiral.

During Wicked Eyes and Wicked Hearts Artemis is able to be recruited as a companion. She is able to be spoken to at Halamshiral as one of Briala's closest advisors. Artemis can be found speaking to Leliana later, whereupon the latter will divulge information to the Inquisitor of their storied past during the Fifth Blight.

It is during this dialogue that Artemis is able to be recruited. Leliana will offer Artemis a place among her spies given that she will also cooperate with Briala's as well. Artemis will accept assisting Leliana and simultaneously spy upon the Orlesian Empire through Briala's network, thus increasing the Inquisition's realm of knowledge tenfold.

Artemis will remain with the Inquisition throughout the rest of the storyline. She can be found frequently in the tower of Skyhold sitting at a table with books and research among the birds.

Conditionally, Artemis and Leliana may engage in a secretive relationship, but this is only discerned by happenstance when Josephine offhandedly mentions their energy in a conversation--quickly followed by a very visible realization between herself and the Inquisitor.

Choices/approval:

Approves of Sera, Cole, Iron Bull, Vivienne, Josephine, Blackwall, Solas

Uncertain of Cassandra, Dorian, Varric

Disapproves of Cullen

Prefers that Cole remains a spirit

Approves allying with the mages

Disapproves conscripting mages

Disapproves allying with the templars

Save the Chargers

Do not allow Cullen to take lyrium

Leave Stroud in the Fade

Greatly approves conscripting the Wardens

Greatly disapproves banishing the Wardens

Approves Celene reconciled with Briala, approves public truce, approves Gaspard puppeted by Briala

Approves of the Inquisitor drinking of the Well of Sorrows

Approves of Leliana as Divine Victoria

Disapproves of Vivienne as Divine Victoria

Disapproves of Cassandra as Divine Victoria

Approves of the Inquisition being disbanded

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

SOME OF OUR FAVORITE SOLD PAINTINGS - NEXT:

JOSEPH CARAUD

(1821 - 1905)

Midday Stroll

Oil on canvas

38 x 26 inches

Signed & dated 1874

https://rehs.com/Joseph_Caraud_Midday_Stroll.html

Joseph Caraud was a French painter born in 1821 and is best known for his paintings of fashionable and well-dressed women from the upper class. His paintings are often set in elegant settings and depict the leisurely activities of his subjects.

"Midday Stroll" is a masterful example of Joseph Caraud's skill as a painter. The use of color is particularly striking, with the pink and white of the woman's dress and parasol contrasting beautifully against the lush greenery and architectural elements in the background. The woman's serene and contemplative expression adds depth and emotion to the painting.

The attention to detail is also impressive, with the intricate patterns on the woman's dress and the delicate features of the small dog she holds. The composition of the painting is balanced, with the large urn to the woman's right providing a counterpoint to her figure and adding to the sense of elegance and luxury.

#joseph caraud#dogs#dog#formal garden#garden#french art#simpler times#pets#elegant woman#fine art#fineart#work of art#art work#rehsgalleries#19th century art#figurative art#genre painting

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

How do I determine the right Urn size for My Pet’s Ashes?

This is among the most significant steps that a pet owner has to take after the death of a dear companion, and it is selecting the proper urn to settle the remaining components of the pet’s body. Figuring out how your pet's remains will fit into the urn that you want to buy leads to the question, What size urn do I need? This question helps provide peace of mind and ensures one is treated properly. At Spirit Pet Urn, we know this may not be easy, so we want to guide you through the process.

0 notes

Note

Teatime Tuesday: "I've heard something about secret treasure troves out there on the Isles. Come into anything good or are the rumors a bit inflated?"

Zeehva offered a cheeky grin at the question. The dragon isles were by far her favorite place at the moment, but an injury to LuLus leg had them back in the city. "You'd think large dragons wouldn't be all that great at hiding things.. but they actually are.. I've found so many things, but it isn't all gold and gemstones like the rumors say. Sometimes it's a box filled with items that help sentimental value to the dragon. But there are things hidden everywhere, you just have to know where to look. My favorite find so far is a wooden carving of a bakar, those large dogs in the plains, that doubled as an urn.. I found it near a ruined burial ground. I was tempted to keep it but thought better of it and instead remade a makeshift grave for it. Whoever owned the bakar, I'm sure they'd appreciate him remaining close to home. I've also found a few maps that Im working on deciphering.. they've got me stumped at the moment though."

Thank you @safrona-shadowsun

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

[The DragonBall fan boys have to be the grossest fan boys, and that's beating hentai fan boys. Under the cut because. Good fucking grief it's gross. If you're an actual Goku fan, i suggest avoiding this one. Goku isn't my favorite character, but I like him, and this made me want to tear off my own limbs and eat them.]

[So I'm absolutely not surprised that this kind of garbage is created and spewed by this fucking fandom, but this once again proves the fan boys of this series want to project SO HARD onto the characters to live out their gross little fantasies with fictional characters. Which you know. Fine. But theyre doing it this time by tearing a character to ABSOLUTE SHREDS to do it. So they come up with this. That somehow, the most loyal and probably borderline asexual (demisexual maybe? His libido isnt fucking high guys thats obvious and he isnt a damn horn dog) character bangs all the "attractive" women, leaves his wife--who yes is written like shit but is attractive as well and he fucking LOVES HER as the fan boys and writers of at least Super conveniently forget--and has...a couple more kids with three different women? Like this is so fucking nasty I don't know where to BEGIN.

Like...fuck. the art is nasty and hyper-sexualizes at least Vados with big tiddies and her nipples showing through her wedding dress in one image.

Then there's the fucking ChiChi abuse. And you know. I'm not the biggest fan of how ChiChi is written, and I know this is a staple for the fan boys. Toriyama and Toyotaro really just made her a walking, awful stereotype like they've done with Bulma. But good grief. The "artist" first of all is wishy washy with her with this...fucking weird idea of ChiChi being okay with Goku shacking up with Vados, and serving them in bed? Like there is so much wrong with that from the obvious to like some gross societal ideas that once a woman reaches a certain age she's only worthwhile in a servile role. Unless they look like Bulma that is, who abuses the dragonballs to maintain her youth a d appearance BUT you get me. And despite that, the artist still has Beerus kill her for some reason? Because of course. And then the picture they have of her above the milk jar that I imagine is supposed to be her urn (even though I'm pretty sure a Hakai leaves nothing behind but why am I even trying to find a shred of something that is potentially accurate to the lore in this, when this is already steaming hot garbage and the lore is inconsistent anyway) is of her being angry. Like...fucking God. The idea that Goku doesn't love ChiChi is atrocious and flat out wrong, and he would NEVER select a picture like that to honor her. But I guess at this point who fucking cares because he's brought his hot angel mommy into their marriage home, so who cares about a little more disrespect, right? And that's not mentioning how the rest of his family is just a-okay with this.

I don't even know what to say about Heles and the Zeno baby. Like....wtf. you were fully into this Vados idea but now he's having a kid with Heles who he....literally never talked to. I'm not sure he ever really saw her.

I'm honestly a little surprised Bulma isn't somehow included in this atrocity. I say a little because she's probably not because that would mean taking their king Vegeta's wife from him and we can't have that. Also like...what does it say about the fan boys' masculinity when they want to make their Shonen anime into a literal, raunchy soap opera rather than a series about overpowered warriors fighting evil? Idk but that's not very manly....🙄🙄🙄 (disclaimer: I don't actually care about that kind of thing and men can absolutely enjoys soap operas; I only bring it up because they care about their very fragile masculinity being challenged). I mean these are probably the same people that whine and bitch about the filler in Z that's by and large actually not bad but stan everything Super has to offer, even the absolutely trash filler.

This pervasive shit is what makes it so hard to be a fan of this series, especially as a girl who grew into a woman watching this series since she was 6. And like yeah. Sure. Toriyama wasn't writing this shit for us. The target audience was boys. But damn. I know Toriyama and apparently Toyotaro are a lost cause on the sexist front, but it would be really nice if the fans didn't take their sexism and dial it up to 9000.]

#.:ooc:.#.:discourse:.#gross ass shit ahoy#im sorry i had to rant#if youre a goku fan i suggest not looking under the cut

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

~ 💖 ASK GAME 💖 ~

(ty for the tag lilah!! <3)

📷 What’s set as your phone’s lockscreen? currently, emo hello kitty to match my johnnie homescreen

🍫 Cheese or chocolate? lowkey allergic to both but chocolate!

✨ Do you have any nicknames? quinn, q-tip? quinny wuinny

🎵 Last song you listened to? willow by taylor swift!

✏️ Have you ever written fanfiction? nooo totally not….(yes)

😏 Are you on discord? mhm!

💛 Do you have any piercings? yes! 3!

🐰 What do you think says the most about a person? how they react to you asking for space tbh

🍪 If you were a cookie, what kind would you be? gingerbread!

🐶 Are you more of a dog person or a cat person? DOGS.

🎧 Headphones or earbuds? earbuds!

🌼 What’s the last thing you said out loud? “could you write a headcannons of johnnie sleeping with a lock of hair🤓” (don’t ask)

🙃 What’s a weird fact that you know? poodle’s pom-poms are technically spelled ponpoms !!

🦉 Are you a morning person or a night owl? night owl <:

🧸 Favorite place to nap? my grandmas bed

🏳️🌈 Are you a member of the LGBTQIA+ community? yup ! queer and nonbinary !

🦋 Describe yourself in three words. silly, sassy annnddd inquisitive?

👖 Jeans or sweatpants? jeans!

🥤 What’s your go-to Starbucks order? boycott starbucks!! 🍉 so i’ll give you guys my dutch bros order, large palm beach green tea!

🧡 A color you can’t stand? yellow😠

💎 What’s your most prized possession? my esa’s urn 💖

☕ Coffee or tea? tea!

🦖 Favorite extinct animal? titanaboa!

🌙 How long have you been on tumblr? a WHILEEEE but this is my first solo account!

🌴 Desert island item? maybe a boat…?

🐸 Describe your aesthetic. farmers daughter! gingham, lace, dark secrets!

🔮 What’s your dream job? ideally a puppy trainer

💙 Relationship status? exclusive!

🌿 Describe your favorite outfit. short black romper-dress and cowgirl boots

🎤 Is there a song you know all the lyrics to? without me, eminem

🤎 What color is your hair? brown with natural copper highlights!

💌 Do you talk to yourself? oh all the time

💄 Do you wear makeup? yes!

🌸 Best compliment you ever received? probably that i was really good at writing c:

💞 @ your favorite blog. @sunlitsabotage @sugar4yummy

~ 💖 ASK GAME 💖 ~

📷 What’s set as your phone’s lockscreen?

🍫 Cheese or chocolate?

✨ Do you have any nicknames?

🎵 Last song you listened to?

✏️ Have you ever written fanfiction?

😏 Are you on discord?

💛 Do you have any piercings?

🐰 What do you think says the most about a person?

🍪 If you were a cookie, what kind would you be?

🐶 Are you more of a dog person or a cat person?

🎧 Headphones or earbuds?

🌼 What’s the last thing you said out loud?

🙃 What’s a weird fact that you know?

🦉 Are you a morning person or a night owl?

🧸 Favorite place to nap?

🏳️🌈 Are you a member of the LGBTQIA+ community?

🦋 Describe yourself in three words.

👖 Jeans or sweatpants?

🥤 What’s your go-to Starbucks order?

🧡 A color you can’t stand?

💎 What’s your most prized possession?

☕ Coffee or tea?

🦖 Favorite extinct animal?

🌙 How long have you been on tumblr?

🌴 Desert island item?

🐸 Describe your aesthetic.

🔮 What’s your dream job?

💙 Relationship status?

🌿 Describe your favorite outfit.

🎤 Is there a song you know all the lyrics to?

🤎 What color is your hair?

💌 Do you talk to yourself?

💄 Do you wear makeup?

🌸 Best compliment you ever received?

💞 @ your favorite blog.

Reblogs are appreciated!

43K notes

·

View notes

Text

Grant Avenue - Flower Drum Song

youtube

Long Line - for - Employee

Runners - Better - Location

Bayfront Park

Their Kids - Running - Cute

1 male looks Thai American

As usual - Alone

Their Loss

Greeks - Today

Kids 4 Work

Not allowed Art & Running

Greece - Land - Dying

Real Greek - awarded by

Ancient Greek King

Alexander

Greatest Awards for

Runners

2nd Greatest - Art

Their Urns - Greek Art

Sculptors - Plates Vases

Kids awarded

Runners - Artists

Hallmark

Today - Old Grandpas

Despise - Mixed Breed

Athens - My Roots

'Wonder Woman'

Berlin Germany

Kid - Me - Fast Mountain

Runner - Record - Fast

Based - American Film

Blonde - couldn't beat

Her dog in running

Became School Track

Running Champ

Walking 2 Gov't Center

Restrooms

Brickell - McDonald's

Bus 7 - goes 2 Biscayne Blvd

Skipping - Dolphin Mall then

Checking - Amazon Delivery

Getting - $21.38 - Gift Card

Soon - Staying here

Brickell - Downtown Miami

Jesus is Lord - Korea KR

Today - Miami - Brags

They're Employed

Running miles

Strong Americans

Red Coach 2 Naples

Most Beautiful City of

The USA - SW Florida

Near Gulf of Mexico

Over 19,000 people

Original Jolly England

Golf Capital of World

Mint & Moon

Official Sport -Golf

2nd - Aikido Japan

Show of Skill

Not against ea other

3rd - Wushu - China

Team USA

Headquarters - Snow

Carmel - Indiana

Team - Carmel

Team - Naples

Competes 2b Official

Team USA - vs - ours

Team Hong Kong Island

'Winner takes All'

Each Member - Winner

Diamond Tear bottom of

Diamond Necklace - Gold

Wins Gold

Each Member - Gets

$500 Billion - x 5

Tax Paid

Bouquet of Flowers

Small Diamond Trophies

Major - 3 Large Diamond

Official Trophies

One on Display

$500 Billion per year for

Display - Tax Paid

Photographs of Team

Mint & Moon

Naples FL

Headquarters

Carmel Indiana

April Snow

Carmel - LLC

Zen Business

Registered Agent

Our Future Better than

Miami FL - Oppressive

Pit - Ugly - Violent USA

Jesus is Lord - Korea KR

0 notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: COPY - Large engravable stainless cremation urn ⚱️.

0 notes